Old School Design Tool: Scale Model

Brianna Cutts, Design Principal

I remember spending hours working at my tiny workbench in the garage of my childhood home, carefully crafting miniature furniture and hand-drawn magazines for my dollhouse.

This hands-on skill eventually made it into classroom assignments, most notably for a 5th grade assignment about the Roman Empire where I made a small diorama capturing the Shakespearean interpretation of the suspenseful “Et tu, Brute?” moment in which Julius Caesar realizes, during his assassination, that he’s been betrayed by his friend Brutus. I even added food coloring blood for extra realism.

Build a Model: Communicate a Concept

While dioramas can be a powerful tool for communicating stories in museums, they are also an essential tool for creating museum exhibits.

Computer rendering software lets us fly through spaces with extraordinary realism, providing a powerful selling point for proposed designs. But how do we create those designs that inform the rendering? Sketches and drawings communicate the intent of a design, but only in a two-dimensional format. A scale model brings the design to life, placing the design within a realistic context and providing a more comprehensive perspective of the design.

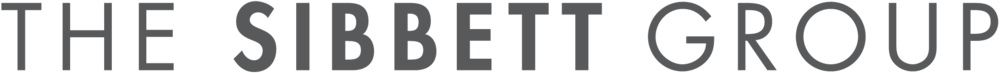

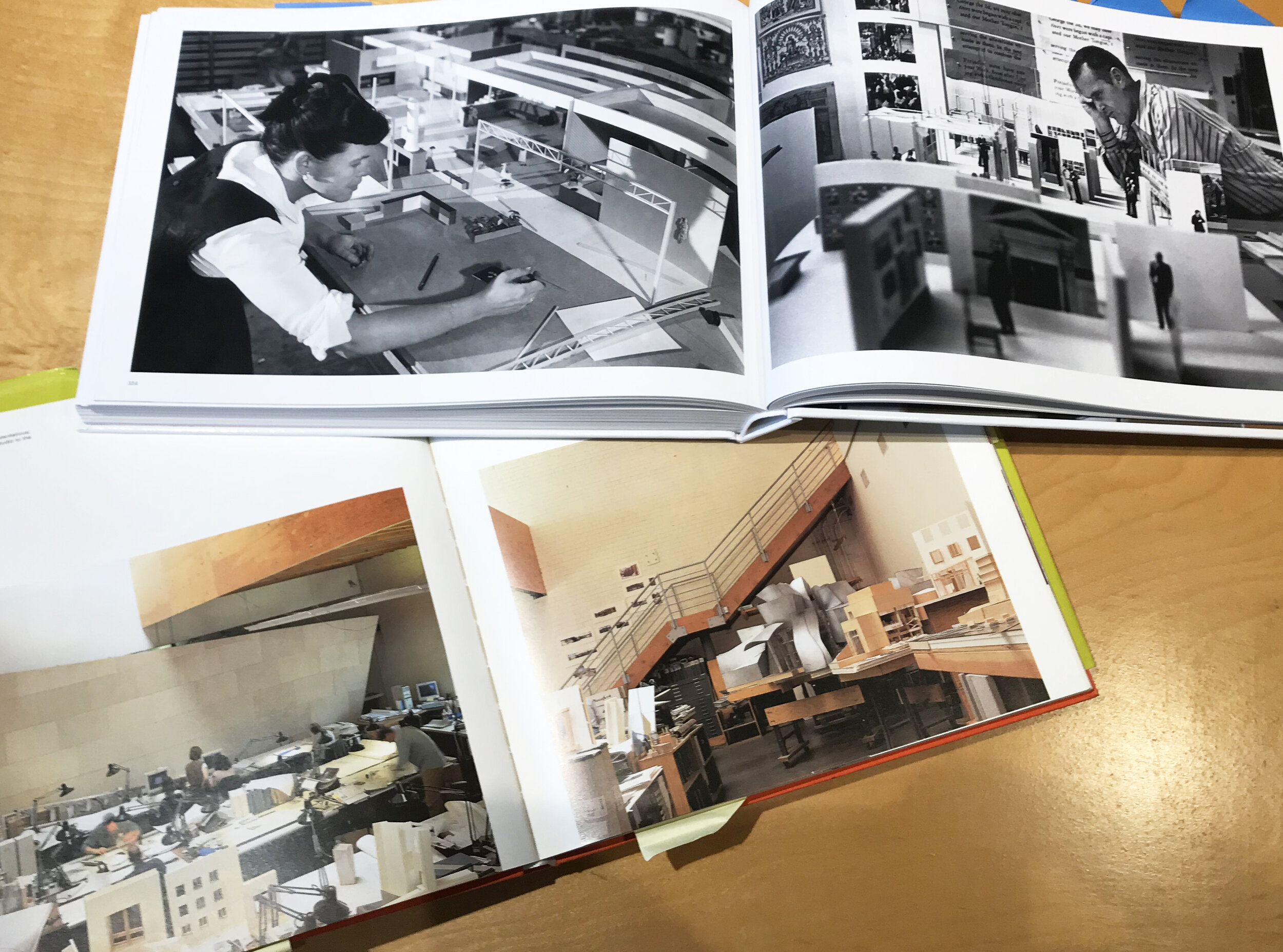

While architects and designers use rendering software to describe three-dimensional spaces, they also create scale models to better understand proportions, spatial relationships and material options. The architecture office of Frank Gehry is known for creating conceptual models to communicate unusual forms created by their structures. For exhibit designers, the designers Charles and Ray Eames provide unique inspiration, having created incredible scale models including a conceptual model for their 1961 exhibition Mathematica: A World of Numbers… and Beyond.

Choose a Size: Design at Scale

Scale models can vary in size, mostly determined by the level of desired detail and the storage capacity of a workspace. For those building models without extensive training or tools, selecting a simple scale such as 1” = 1’ or ½” = 1’ can be a good place to start.

A base plan provides the footprint of a space, while elevations provide views of the walls. Simple models can be built with paper, assembling the floors and walls to create a three-dimensions space. More advanced models can be built using more solid materials, such as foam core or balsa wood. If you plan on using sharp tools to cut your model pieces, remember to use caution!

Design a Space: Bring it to Life

Once the model takes a three-dimensional form, add details such as furnishings, graphics and people (notice Charles Eames seated on the plan to the right). Modify the layout to explore different design solutions, adding people to get a feel for space needs and adjacencies.

Capture views through your model using photography, which helps to imagine how a future visitor will experience your exhibition.